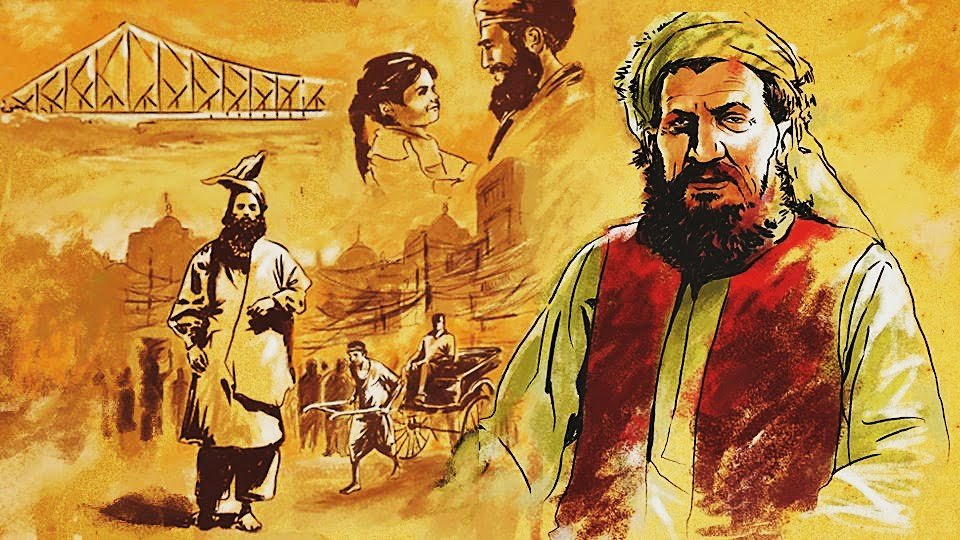

The Last Love / अन्तिम प्यार

यह कहानी रवींद्रनाथ टैगोर द्वारा लिखी गई है!

आर्ट स्कूल के प्रोफेसर मनमोहन बाबू घर पर बैठे मित्रों के साथ मनोरंजन कर रहे थे, ठीक उसी समय योगेश बाबू ने कमरे में प्रवेश किया।

योगेश बाबू अच्छे चित्रकार थे, उन्होंने अभी थोड़े समय पूर्व ही स्कूल छोड़ा था। उन्हें देखकर एक व्यक्ति ने कहा-योगेश बाबू! नरेन्द्र क्या कहता है, आपने सुना कुछ?

योगेश बाबू ने आराम-कुर्सी पर बैठकर पहले तो एक लम्बी सांस ली, पश्चात् बोले-क्या कहता है?

नरेन्द्र कहता है- बंग-प्रान्त में उसकी कोटि का कोई भी चित्रकार इस समय नहीं है।

ठीक है, अभी कल का छोकरा है न। हम लोग तो जैसे आज तक घास छीलते रहे हैं। झुंझलाकर योगेश बाबू ने कहा।

जो लड़का बातें कर रहा था, उसने कहा-केवल यही नहीं, नरेन्द्र आपको भी सम्मान की दृष्टि से नहीं देखता।

योगेश बाबू ने उपेक्षित भाव से कहा-क्यों, कोई अपराध!

वह कहता है आप आदर्श का ध्यान रखकर चित्र नहीं बनाते।

तो किस दृष्टिकोण से बनाता हूं?

दृष्टिकोण…?

रुपये के लिए।

योगेश ने एक आंख बन्द करके कहा-व्यर्थ! फिर आवेश में कान के पास से अपने अस्त-व्यस्त बालों की ठीक कर बहुत देर तक मौन बैठा रहा। चीन का जो सबसे बड़ा चित्रकार हुआ है उसके बाल भी बहुत बड़े थे। यही कारण था कि योगेश ने भी स्वभाव-विरुध्द सिर पर लम्बे-लम्बे बाल रखे हुए थे। ये बाल उसके मुख पर बिल्कुल नहीं भाते थे। क्योंकि बचपन में एक बार चेचक के आक्रमण से उनके प्राण तो बच गये थे। किन्तु मुख बहुत कुरूप हो गया था। एक तो स्याम-वर्ण, दूसरे चेचक के दाग। चेहरा देखकर सहसा यही जान पड़ता था, मानो किसी ने बन्दूक में छर्रे भरकर लिबलिबी दाब दी हो।

कमरे में जो लड़के बैठे थे, योगेश बाबू को क्रोधित देखकर उसके सामने ही मुंह बन्द करके हंस रहे थे।

सहसा वह हंसी योगेश बाबू ने भी देख ली, क्रोधित स्वर में बोले-तुम लोग हंस रहे हो, क्यों?

एक लड़के ने चाटुकारिता से जल्दी-जल्दी कहा-नहीं महाशय! आपको क्रोध आये और हम लोग हंसे, यह भला कभी सम्भव हो सकता है?

ऊंह! मैं समझ गया, अब अधिक चातुर्य की आवश्यकता नहीं। क्या तुम लोग यह कहना चाहते हो कि अब तक तुम सब दांत निकालकर रो रहे थे, मैं ऐसा मूर्ख नहीं हूं? यह कहकर उन्होंने आंखें बन्द कर ली।

लड़कों ने किसी प्रकार हंसी रोककर कहा-चलिए यों ही सही, हम हंसते ही थे और रोते भी क्यों? पर हम नरेन्द्र के पागलपन को सोचकर हंसते थे। वह देखो मास्टर साहब के साथ नरेन्द्र भी आ रहा है।

मास्टर साहब के साथ-साथ नरेन्द्र भी कमरे में आ गया।

योगेश ने एक बार नरेन्द्र की ओर वक्र दृष्टि से देखकर मनमोहन बाबू से कहा-महाशय! नरेन्द्र मेरे विषय में क्या कहता है?

मनमोहन बाबू जानते थे कि उन दोनों की लगती है। दो पाषाण जब परस्पर टकराते हैं तो अग्नि उत्पन्न हो ही जाती है। अतएव वह बात को संभालते, मुस्कराते-से बोले-योगेश बाबू, नरेन्द्र क्या कहता है?

नरेन्द्र कहता है कि मैं रुपये के दृष्टिकोण से चित्र बनाता हूं। मेरा कोई आदर्श नहीं है?

मनमोहन बाबू ने पूछा- क्यों नरेन्द्र?

नरेन्द्र अब तक मौन खड़ा था, अब किसी प्रकार आगे आकर बोला-हां कहता हूं, मेरी यही सम्मति है।’

योगेश बाबू ने मुंह बनाकर कहा- बड़े सम्मति देने वाले आये। छोटे मुंह बड़ी बात। अभी कल का छोकरा और इतनी बड़ी-बड़ी बातें।

मनमोहन बाबू ने कहा-योगेश बाबू जाने दीजिए, नरेन्द्र अभी बच्चा है, और बात भी साधारण है। इस पर वाद-विवाद की क्या आवश्यकता है?

योगेश बाबू उसी तरह आवेश में बोले-बच्चा है। नरेन्द्र बच्चा है। जिसके मुंह पर इतनी बड़ी-बड़ी मूंछें हों, वह यदि बच्चा है तो बूढ़ा क्या होगा? मनमोहन बाबू! आप क्या कहते हैं?

एक विद्यार्थी ने कहा-महाशय, अभी जरा देर पहले तो आपने उसे कल का छोकरा बताया था।

योगेश बाबू का मुख क्रोध से लाल हो गया, बोले-कब कहा था?

अभी इससे ज़रा देर पहले।’

झूठ! बिल्कुल झूठ!! जिसकी इतनी बड़ी-बड़ी मूंछें हैं उसे छोकरा कहूं, असम्भव है। क्या तुम लोग यह कहना चाहते हो कि मैं बिल्कुल मूर्ख हूं।

सब लड़के एक स्वर से बोले-नहीं, महाशय! ऐसी बात हम भूलकर भी जिह्ना पर नहीं ला सकते।

मनमोहन बाबू किसी प्रकार हंसी को रोककर बोले- चुप-चुप! गोलमाल न करो।

योगेश बाबू ने कहा- हां नरेन्द्र! तुम यह कहते हो कि बंग-प्रान्त में तुम्हारी टक्कर का कोई चित्रकार नहीं है।

नरेन्द्र ने कहा-आपने कैसे जाना?

तुम्हारे मित्रों ने कहा।

मैं यह नहीं कहता। तब भी इतना अवश्य कहूंगा कि मेरी तरह हृदय-रक्त पीकर बंगाल में कोई चित्र नहीं बनाता।

इसका प्रमाण?

नरेन्द्र ने आवेशमय स्वर में कहा- प्रमाण की क्या आवश्यकता है? मेरा अपना यही विचार है।

तुम्हारा विचार असत्य है।

नरेन्द्र बहुत कम बोलने वाला व्यक्ति था। उसने कोई उत्तर नहीं दिया।

मनमोहन बाबू ने इस अप्रिय वार्तालाप को बन्द करने के लिए कहा- नरेन्द्र इस बार प्रदर्शनी के लिए तुम चित्र बनाओगे ना?

नरेन्द्र ने कहा- विचार तो है।

देखूंगा तुम्हारा चित्र कैसा रहता है?

नरेन्द्र ने श्रध्दा-भाव से उनकी पग-धूलि लेकर कहा- जिसके गुरु आप हैं उसे क्या चिन्ता? देखना सर्वोत्तम रहेगा।

योगेश बाबू ने कहा- राम से पहले रामायण! पहले चित्र बनाओ फिर कहना।

नरेन्द्र ने मुंह फेरकर योगेश बाबू की ओर देखा, कहा कुछ भी नहीं, किन्तु मौन भाव और उपेक्षा ने बातों से कहीं अधिक योगेश के हृदय को ठेस पहुंचाई।

मनमोहन बाबू ने कहा- योगेश बाबू, चाहे आप कुछ भी कहें मगर नरेन्द्र को अपनी आत्मिक शक्ति पर बहुत बड़ा विश्वास है। मैं दृढ़ निश्चय से कह सकता हूं कि यह भविष्य में एक बड़ा चित्रकार होगा।’

नरेन्द्र धीरे-धीरे कमरे से बाहर चला गया।

एक विद्यार्थी ने कहा- प्रोफेसर साहब, नरेन्द्र में किसी सीमा तक विक्षिप्तता की झलक दिखाई देती है।’

मनमोहन बाबू ने कहा- हां, मैं भी मानता हूं। जो व्यक्ति अपने घाव अच्छी तरह प्रकट करने में सफल हो जाता है, उसे सर्व-साधारण किसी सीमा तक विक्षिप्त समझते हैं। चित्र में एक विशेष प्रकार का आकर्षण तथा मोहकता उत्पन्न करने की उसमें असाधारण योग्यता है। तुम्हें मालूम है, नरेन्द्र ने एक बार क्या किया था? मैंने देखा कि नरेन्द्र के बायें हाथ की उंगली से खून का फव्वारा छूट रहा है और वह बिना किसी कष्ट के बैठा चित्र बना रहा है। मैं तो देखकर चकित रह गया। मेरे मालूम करने पर उसने उत्तर दिया कि उंगली काटकर देख रहा था कि खून का वास्तविक रंग क्या है? अजीब व्यक्ति है। तुम लोग इसे विक्षिप्तता कह सकते हो, किन्तु इसी विक्षिप्तता के ही कारण तो वह एक दिन अमर कलाकार कहलायेगा।

योगेश बाबू आंख बन्द करके सोचने लगे। जैसे गुरु वैसे चेले दोनों के दोनों पागल हैं।

नरेन्द्र सोचते-सोचते मकान की ओर चला-मार्ग में भीड़-भाड़ थी। कितनी ही गाड़ियां चली जा रही थीं; किन्तु इन बातों की ओर उसका ध्यान नहीं था। उसे क्या चिन्ता थी? सम्भवत: इसका भी उसे पता न था।

वह थोड़े समय के भीतर ही बहुत बड़ा चित्रकार हो गया, इस थोड़े-से समय में वह इतना सुप्रसिध्द और सर्व-प्रिय हो गया था कि उसके ईष्यालु मित्रों को अच्छा न लगा। इन्हीं ईष्यालु मित्रों में योगेश बाबू भी थे। नरेन्द्र में एक विशेष योग्यता और उसकी तूलिका में एक असाधारण शक्ति है। योगेश बाबू इसे दिल-ही-दिल में खूब समझते थे, परन्तु ऊपर से उसे मानने के लिए तैयार न थे।

इस थोड़े समय में ही उसका इतनी प्रसिध्दि प्राप्त करने का एक विशेष कारण भी था। वह यह कि नरेन्द्र जिस चित्र को भी बनाता था अपनी सारी योग्यता उसमें लगा देता था उसकी दृष्टि केवल चित्र पर रहती थी, पैसे की ओर भूलकर भी उसका ध्यान नहीं जाता था। उसके हृदय की महत्वाकांक्षा थी कि चित्र बहुत ही सुन्दर हो। उसमें अपने ढंग की विशेष विलक्षणता हो। मूल्य चाहे कम मिले या अधिक। वह अपने विचार और भावनाओं की मधुर रूप-रेखायें अपने चित्र में देखता था। जिस समय चित्र चित्रित करने बैठता तो चारों ओर फैली हुई असीम प्रकृति और उसकी सारी रूप-रेखायें हृदय-पट से गुम्फित कर देता। इतना ही नहीं; वह अपने अस्तित्व से भी विस्मृत हो जाता। वह उस समय पागलों की भांति दिखाई पड़ता और अपने प्राण तक उत्सर्ग कर देने से भी उस समय सम्भवत: उसको संकोच न होता। यह दशा उस समय की एकाग्रता की होती। वास्तव में इसी कारण से उसे यह सम्मान प्राप्त हुआ। उसके स्वभाव में सादगी थी, वह जो बात सादगी से कहता, लोग उसे अभिमान और प्रदर्शनी से लदी हुई समझते। उसके सामने कोई कुछ न कहता परन्तु पीछे-पीछे लोग उसकी बुराई करने से न चूकते, सब-के-सब नरेन्द्र को संज्ञाहीन-सा पाते, वह किसी बात को कान लगाकर न सुनता, कोई पूछता कुछ और वह उत्तर देता कुछ और ही। वह सर्वदा ऐसा प्रतीत होता जैसे अभी-अभी स्वप्न देख रहा था और किसी ने सहसा उसे जगा दिया हो, उसने विवाह किया और एक लड़का भी उत्पन्न हुआ, पत्नी बहुत सुन्दर थी, परन्तु नरेन्द्र को गार्हस्थिक जीवन में किसी प्रकार का आकर्षण न था, तब भी उसका हृदय प्रेम का अथाह सागर था, वह हर समय इसी धुन में रहता था कि चित्रकला में प्रसिध्दि प्राप्त करे। यही कारण था कि लोग उसे पागल समझते थे। किसी हल्की वस्तु को यदि पानी में जबर्दस्ती डुबो दो तो वह किसी प्रकार भी न डूबेगी, वरन ऊपर तैरती रहेगी। ठीक यही दशा उन लोगों की होती है जो अपनी धुन के पक्के होते हें। वे सांसारिक दु:ख-सुख में किसी प्रकार डूबना नहीं जानते। उनका हृदय हर समय कार्य की पूर्ति में संलग्न रहता है।

नरेन्द्र सोचते-सोचते अपने मकान के सामने आ खड़ा हुआ। उसने देखा कि द्वार के समीप उसका चार साल का बच्चा मुंह में उंगली डाले किसी गहरी चिन्ता में खड़ा है। पिता को देखते ही बच्चा दौड़ता हुआ आया और दोनों हाथों से नरेन्द्र को पकड़कर बोला- बाबूजी!

क्यों बेटा?

बच्चे ने पिता का हाथ पकड़ लिया और खींचते हुए कहा- बाबूजी, देखो हमने एक मेंढक मारा है जो लंगड़ा हो गया है…

नरेन्द्र ने बच्चे को गोद में उठाकर कहा-तो मैं क्या करूं? तू बड़ा पाजी है।

बच्चे ने कहा- वह घर नहीं जा सकता-लंगड़ा हो गया है, कैसे जाएगा? चलो उसे गोद में उठाकर घर पहुंचा दो।

नरेन्द्र ने बच्चे को गोद में उठा लिया और हंसते-हंसते घर में ले गया।

एक दिन नरेन्द्र को ध्यान आया कि इस बार की प्रदर्शनी में जैसे भी हो अपना एक चित्र भेजना चाहिए। कमरे की दीवार पर उसके हाथ के कितने ही चित्र लगे हुए थे। कहीं प्राकृतिक दृश्य, कहीं मनुष्य के शरीर की रूप-रेखा, कहीं स्वर्ण की भांति सरसों के खेत की हरियाली, जंगली मनमोहक दृश्यावलि और कहीं वे रास्ते जो छाया वाले वृक्षों के नीचे से टेढ़े-तिरछे होकर नदी के पास जा मिलते थे। धुएं की भांति गगनचुम्बी पहाड़ों की पंक्ति, जो तेज धूप में स्वयं झुलसी जा रही थीं और सैकड़ों पथिक धूप से व्याकुल होकर छायादार वृक्षों के समूह में शरणार्थी थे, ऐसे कितने ही दृश्य थे। दूसरी ओर अनेकों पक्षियों के चित्र थे। उन सबके मनोभाव उनके मुखों से प्रकट हो रहे थे। कोई गुस्से में भरा हुआ, कोई चिन्ता की अवस्था में तो कोई प्रसन्न-मुख।

कमरे के उत्तरीय भाग में खिड़की के समीप एक अपूर्ण चित्र लगा हुआ था; उसमें ताड़ के वृक्षों के समूह के समीप सर्वदा मौन रहने वाली छाया के आश्रय में एक सुन्दर नवयुवती नदी के नील-वर्ण जल में अचल बिजली-सी मौन खड़ी थी। उसके होंठों और मुख की रेखाओं में चित्रकार ने हृदय की पीड़ा अंकित की थी। ऐसा प्रतीत होता था मानो चित्र बोलना चाहता है, किन्तु यौवन अभी उसके शरीर में पूरी तरह प्रस्फुटित नहीं हुआ है।

इन सब चित्रों में चित्रकार के इतने दिनों की आशा और निराशा मिश्रित थी, परन्तु आज उन चित्रों की रेखाओं और रंगों ने उसे अपनी ओर आकर्षित न किया। उसके हृदय में बार-बार यही विचार आने लगे कि इतने दिनों उसने केवल बच्चों का खेल किया है। केवल कागज के टुकड़ों पर रंग पोता है। इतने दिनों से उसने जो कुछ रेखाएं कागज पर खींची थीं, वे सब उसके हृदय को अपनी ओर आकर्षित न कर सकी, क्योंकि उसके विचार पहले की अपेक्षा बहुत उच्च थे। उच्च ही नहीं बल्कि बहुत उच्चतम होकर चील की भांति आकाश में मंडराना चाहते थे। यदि वर्षा ऋतु का सुहावना दिन हो तो क्या कोई शक्ति उसे रोक सकती थी? वह उस समय आवेश में आकर उड़ने की उत्सुकता में असीमित दिशाओं में उड़ जाता। एक बार भी फिरकर नहीं देखता। अपनी पहली अवस्था पर किसी प्रकार भी वह सन्तुष्ट नहीं था। नरेन्द्र के हृदय में रह-रहकर यही विचार आने लगा। भावना और लालसा की झड़ी-सी लग गई।

उसने निश्चय कर लिया कि इस बार ऐसा चित्र बनाएगा। जिससे उसका नाम अमर हो जाये। वह इस वास्तविकता को सबके दिलों में बिठा देना चाहता था कि उसकी अनुभूति बचपन की अनुभूति नहीं है।

मेज पर सिर रखकर नरेन्द्र विचारों का ताना-बाना बुनने लगा। वह क्या बनायेगा? किस विषय पर बनायेगा? हृदय पर आघात होने से साधारण प्रभाव पड़ता है। भावनाओं के कितने ही पूर्ण और अपूर्ण चित्र उसकी आंखों के सामने से सिनेमा-चित्र की भांति चले गये, परन्तु किसी ने भी दमभर के लिए उसके ध्यान को अपनी ओर आकर्षित न किया। सोचते-सोचते सन्ध्या के अंधियारे में शंख की मधुर ध्वनि ने उसको मस्त कर देने वाला गाना सुनाया। इस स्वर-लहरी से नरेन्द्र चौंककर उठ खड़ा हुआ। पश्चात् उसी अंधकार में वह चिन्तन-मुद्रा में कमरे के अन्दर पागलों की भांति टहलने लगा। सब व्यर्थ! महान प्रयत्न करने के पश्चात् भी कोई विचार न सूझा।

रात बहुत जा चुकी थी। अमावस्या की अंधेरी में आकाश परलोक की भांति धुंधला प्रतीत होता था। नरेन्द्र कुछ खोया-खोया-सा पागलों की भांति उसी ओर ताकता रहा।

बाहर से रसोइये ने द्वार खटखटाकर कहा- बाबूजी!

चौंककर नरेन्द्र ने पूछा- कौन है?

बाबूजी भोजन तैयार है, चलिये।

झुंझलाते हुए नरेन्द्र ने कटु स्वर में कहा- मुझे तंग न करो। जाओ मैं इस समय न खाऊंगा।

कुछ थोड़ा-सा।

मैं कहता हूं बिल्कुल नहीं। और निराश-मन रसोइया भारी कदमों से वापस लौट गया और नरेन्द्र ने अपने को चिन्तन-सागर में डुबो दिया। दुनिया में जिसको ख्याति प्राप्त करने का व्यसन लग गया हो उसको चैन कहां?

एक सप्ताह बीत गया। इस सप्ताह में नरेन्द्र ने घर से बाहर कदम न निकाला। घर में बैठा सोचता रहता- किसी-न-किसी मन्त्र से तो साधना की देवी अपनी कला दिखाएगी ही।

इससे पूर्व किसी चित्र के लिऐ उसे विचार-प्राप्ति में देर न लगती थी, परन्तु इस बार किसी तरह भी उसे कोई बात न सूझी। ज्यों-ज्यों दिन व्यतीत होते जाते थे वह निराश होता जाता था? केवल यही क्यों? कई बार तो उसने झुंझलाकर सिर के बाल नोंच लिये। वह अपने आपको गालियां देता, पृथ्वी पर पेट के बल पड़कर बच्चों की तरह रोया भी परंतु सब व्यर्थ।

प्रात:काल नरेन्द्र मौन बैठा था कि मनमोहन बाबू के द्वारपाल ने आकर उसे एक पत्र दिया। उसने उसे खोलकर देखा। प्रोफेसर साहब ने उसमें लिखा था-

प्रिय नरेन्द्र,

प्रदर्शनी होने में अब अधिक दिन शेष नहीं हैं। एक सप्ताह के अन्दर यदि चित्र न आया तो ठीक नहीं। लिखना, तुम्हारी क्या प्रगति हुई है और तुम्हारा चित्र कितना बन गया है?

योगेश बाबू ने चित्र चित्रित कर दिया है। मैंने देखा है, सुन्दर है, परन्तु मुझे तुमसे और भी अच्छे चित्र की आशा है। तुमसे अधिक प्रिय मुझे और कोई नहीं। आशीर्वाद देता हूं, तुम अपने गुरु की लाज रख सको।

इसका ध्यान रखना। इस प्रदर्शनी में यदि तुम्हारा चित्र अच्छा रहा तो तुम्हारी ख्याति में कोई बाधा न रहेगी। तुम्हारा परिश्रम सफल हो, यही कामना है।

-मनमोहन

पत्र पढ़कर नरेन्द्र और भी व्याकुल हुआ। केवल एक सप्ताह शेष है और अभी तक उसके मस्तिष्क में चित्र के विषय में कोई विचार ही नहीं आया। खेद है अब वह क्या करेगा?

उसे अपने आत्म-बल पर बहुत विश्वास था, पर उस समय वह विश्वास भी जाता रहा। इसी तुच्छ शक्ति पर वह दस व्यक्तियों में सिर उठाए फिरता रहा?

उसने सोचा था अमर कलाकार बन जाऊंगा, परन्तु वाह रे दुर्भाग्य! अपनी अयोग्यता पर नरेन्द्र की आंखों में आंसू भर आये।

रोगी की रात जैसे आंखों में निकल जाती है उसकी वह रात वैसे ही समाप्त हुई। नरेन्द्र को इसका तनिक भी पता न हुआ। उधर वह कई दिनों से चित्रशाला ही में सोया था। नरेन्द्र के मुख पर जागरण के चिन्ह थे। उसकी पत्नी दौड़ी-दौड़ी आई और शीघ्रता से उसका हाथ पकड़कर बोली- अजी बच्चे को क्या हो गया है, आकर देखो तो।

नरेन्द्र ने पूछा- क्या हुआ?

पत्नी लीला हांफते हुए बोली- शायद हैजा! इस प्रकार खड़े न रहो, बच्चा बिल्कुल अचेत पड़ा है।

बहुत ही अनमने मन से नरेन्द्र शयन-कक्ष में प्रविष्ट हुआ।

बच्चा बिस्तर से लगा पड़ा था। पलंग के चारों ओर उस भयानक रोग के चिन्ह दृष्टिगोचर हो रहे थे। लाल रंग दो घड़ी में ही पीला हो गया था। सहसा देखने से यही ज्ञात होता था जैसे बच्चा जीवित नहीं है। केवल उसके वक्ष के समीप कोई वस्तु धक-धक कर रही थी, और इस क्रिया से ही जीवन के कुछ चिन्ह दृष्टिगोचर होते थे।

वह बच्चे के सिरहाने सिर झुकाकर खड़ा हो गया।

लीला ने कहा- इस तरह खड़े न रहो। जाओ, डॉक्टर को बुला लाओ।

मां की आवाज सुनकर बच्चे ने आंखें मलीं। भर्राई हुई आवाज में बोला- मां! ओ मां!!

मेरे लाल! मेरी पूंजी। क्या कह रहा है? कहते-कहते लीला ने दोनों हाथों से बच्चे को अपनी गोद से चिपटा लिया। मां के वक्ष पर सिर रखकर बच्चा फिर पड़ा रहा।

नरेन्द्र के नेत्र सजल हो गए। वह बच्चे की ओर देखता रहा।

लीला ने उपालम्भमय स्वर में कहा-अभी तक डॉक्टर को बुलाने नहीं गये?

नरेन्द्र ने दबी आवाज में कहा-ऐं…डॉक्टर?

पति की आवाज का अस्वाभाविक स्वर सुनकर लीला ने चकित होते हुए कहा-क्या?

कुछ नहीं।

जाओ, डॉक्टर को बुला लाओ।

अभी जाता हूं।

नरेन्द्र घर से बाहर निकला।

घर का द्वार बन्द हुआ। लीला ने आश्चर्य-चकित होकर सुना कि उसके पति ने बाहर से द्वार की जंजीर खींच ली और वह सोचती रही- यह क्या?

नरेन्द्र चित्रशाला में प्रविष्ट होकर एक कुर्सी पर बैठ गया।

दोनों हाथों से मुंह ढांपकर वह सोचने लगा। उसकी दशा देखकर ऐसा लगता था कि वह किसी तीव्र आत्मिक पीड़ा से पीड़ित है। चारों ओर गहरे सूनेपन का राज्य था। केवल दीवार लगी हुई घड़ी कभी न थकने वाली गति से टिक-टिक कर रही थी और नरेन्द्र के सीने के अन्दर उसका हृदय मानो उत्तर देता हुआ कह रहा था- धक! धक! सम्भवत: उसके भयानक संकल्पों से परिचित होकर घड़ी और उसका हृदय परस्पर कानाफूसी कर रहे थे। सहसा नरेन्द्र उठ खड़ा हुआ। संज्ञाहीन अवस्था में कहने लगा- क्या करूं? ऐसा आदर्श फिर न मिलेगा, परन्तु …वह तो मेरा पुत्र है।

वह कहते-कहते रुक गया। मौन होकर सोचने लगा। सहसा मकान के अन्दर से सनसनाते हुए बाण की भांति ‘हाय’ की हृदयबेधक आवाज उसके कानों में पहुंची।

मेरे लाल! तू कहां गया?

जिस प्रकार चिल्ला टूट जाने से कमान सीधी हो जाती है, चिन्ता और व्याकुलता से नरेन्द्र ठीक उसी तरह सीधा खड़ा हो गया। उसके मुख पर लाली का चिन्ह तक न था, फिर कान लगाकर उसने आवाज सुनी, वह समझ गया कि बच्चा चल बसा।

मन-ही-मन में बोला- भगवान! तुम साक्षी हो, मेरा कोई अपराध नहीं।

इसके बाद वह अपने सिर के बालों को मुट्ठी में लेकर सोचने लगा। जैसे कुछ समय पश्चात् ही मनुष्य निद्रा से चौंक उठता है उसी प्रकार चौंककर जल्दी-जल्दी मेज पर से कागज, तूलिका और रंग आदि लेकर वह कमरे से बाहर निकल गया।

शयन-कक्ष के सामने एक खिड़की के समीप आकर वह अचकचा कर खड़ा हो गया। कुछ सुनाई देता है क्या? नहीं सब खामोश हैं। उस खिड़की से कमरे का आन्तरिक भाग दिखाई पड़ रहा था। झांककर भय से थर-थर कांपते हुए उसने देखा तो उसके सारे शरीर में कांटे-से चुभ गये। बिस्तर उलट-पुलट हो रहा था। पुत्र से रिक्त गोद किए मां वहीं पड़ी तड़प रही थी।

और इसके अतिरिक्त…मां कमरे में पृथ्वी पर लोटते हुए, बच्चे के मृत शरीर को दोनों हाथों से वक्ष:स्थल के साथ चिपटाए, बाल बिखरे, नेत्र विस्फारित किए, बच्चे के निर्जीव होंठों को बार-बार चूम रही थी।

नरेन्द्र की दोनों आंखों में किसी ने दो सलाखें चुभो दी हों। उसने होंठ चबाकर कठिनता से स्वयं को संभाला और इसके साथ ही कागज पर पहली रेखा खींची। उसके सामने कमरे के अन्दर वही भयानक दृश्य उपस्थित था। संभवत: संसार के किसी अन्य चित्रकार ने ऐसा दृश्य सम्मुख रखकर तूलिका न उठाई होगी।

देखने में नरेन्द्र के शरीर में कोई गति न थी, परन्तु उसके हृदय में कितनी वेदना थी? उसे कौन समझ सकता है, वह तो पिता था।

नरेन्द्र जल्दी-जल्दी चित्र बनाने लगा। जीवन-भर चित्र बनाने में इतनी जल्दी उसने कभी न की। उसकी उंगलियां किसी अज्ञात शक्ति से अपूर्व शक्ति प्राप्त कर चुकी थीं। रूप-रेखा बनाते हुए उसने सुना- बेटा, ओ बेटा! बातें करो, बात करो, जरा एक बार तुम देख तो लो?

नरेन्द्र ने अस्फुट स्वर में कहा- उफ! यह असहनीय है। और उसके हाथ से तूलिका छूटकर पृथ्वी पर गिर पड़ी।

किन्तु उसी समय तूलिका उठाकर वह पुन: चित्र बनाने लगा। रह-रहकर लीला का क्रन्दन-रुदन कानों में पहुंचकर हृदय को छेड़ता और रक्त की गति को मन्द करता और उसके हाथ स्थिर होकर उसकी तूलिका की गति को रोक देते।

इसी प्रकार पल-पर-पल बीतने लगे।

मुख्य द्वार से अन्दर आने के लिए नौकरों ने शोर मचाना शुरू कर दिया था, परन्तु नरेन्द्र मानो इस समय विश्व और विश्वव्यापी कोलाहल से बहरा हो चुका था।

वह कुछ भी न सुन सका। इस समय वह एक बार कमरे की ओर देखता और एक बार चित्र की ओर, बस रंग में तूलिका डुबोता और फिर कागज पर चला देता।

वह पिता था, परन्तु कमरे के अन्दर पत्नी के हृदय से लिपटे हुए मृत बच्चे की याद भी वह धीरे-धीरे भूलता जा रहा था।

सहसा लीला ने उसे देख लिया। दौड़ती हुई खिड़की के समीप आकर दुखित स्वर में बोली-क्या डॉक्टर को बुलाया? जरा एक बार आकर देख तो लेते कि मेरा लाल जीवित है या नहीं…यह क्या? चित्र बना रहे हो?

चौंककर नरेन्द्र ने लीला की ओर देखा। वह लड़खड़ाकर गिर रही थी।

बाहर से द्वार खटखटाने और बार-बार चिल्लाने पर भी जब कपाट न खुले, तो रसोइया और नौकर दोनों डर गये। वे अपना काम समाप्त करके प्राय: संध्या समय घर चले जाते थे और प्रात:काल काम करने आ जाते थे। प्रतिदिन लीला या नरेन्द्र दोनों में से कोई-न-कोई द्वार खोल देता था, आज चिल्लाने और खटखटाने पर भी द्वार न खुला। इधर रह-रहकर लीला की क्रन्दन-ध्वनि भी कानों में आ रही थी।

उन लोगों ने मुहल्ले के कुछ व्यक्तियों को बुलाया। अन्त में सबने सलाह करके द्वार तोड़ डाला।

सब आश्चर्य-चकित होकर मकान में घुसे। जीने से चढ़कर देखा कि दीवार का सहारा लिये, दोनों हाथ जंघाओं पर रखे नरेन्द्र सिर नीचा किए हुए बैठा है।

उनके पैरों की आहट से नरेन्द्र ने चौंककर मुंह उठाया। उसके नेत्र रक्त की भांति लाल थे। थोड़ी देर पश्चात् वह ठहाका मारकर हंसने लगा और सामने लगे चित्र की ओर उंगली दिखाकर बोल उठा- डॉक्टर! डॉक्टर!! मैं अमर हो गया।

दिन बीतते गये, प्रदर्शनी आरम्भ हो गई।

प्रदर्शनी में देखने की कितनी ही वस्तुएं थीं, परन्तु दर्शक एक ही चित्र पर झुके पड़ते थे। चित्र छोटा-सा था और अधूरा भी, नाम था ‘अन्तिम प्यार।’

चित्र में चित्रित किया हुआ था, एक मां बच्चे का मृत शरीर हृदय से लगाये अपने दिल के टुकड़े के चन्दा से मुख को बार-बार चूम रही है।

शोक और चिन्ता में डूबी हुई मां के मुख, नेत्र और शरीर में चित्रकार की तूलिका ने एक ऐसा सूक्ष्म और दर्दनाक चित्र चित्रित किया कि जो देखता उसी की आंखों से आंसू निकल पड़ते। चित्र की रेखाओं में इतनी अधिक सूक्ष्मता से दर्द भरा जा सकता है, यह बात इससे पहले किसी के ध्यान में न आई थी।

इस दर्शक-समूह में कितने ही चित्रकार थे। उनमें से एक ने कहा- देखिए योगेश बाबू, आप क्या कहते हैं?

योगेश बाबू उस समय मौन धारण किए चित्र की ओर देख रहे थे, सहसा प्रश्न सुनकर एक आंख बन्द करके बोले- यदि मुझे पहले से ज्ञात होता तो मैं नरेन्द्र को अपना गुरु बनाता।

दर्शकों ने धन्यवाद, साधुवाद और वाह-वाह की झड़ी लगा दी; परन्तु किसी को भी मालूम न हुआ कि उस सज्जन पुरुष का मूल्य क्या है, जिसने इस चित्र को चित्रित किया है।

किस प्रकार चित्रकार ने स्वयं को धूलि में मिलाकर रक्त से इस चित्र को रंगा है, उसकी यह दशा किसी को भी ज्ञात न हो सकी।